GRAPH BOOKS: PRINTED MATTER FROM RADICAL ART AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS.

FEMINIST HISTORIANS OF MATERIAL CULTURE.

Cocktail

Silvia Guerrico, 1932

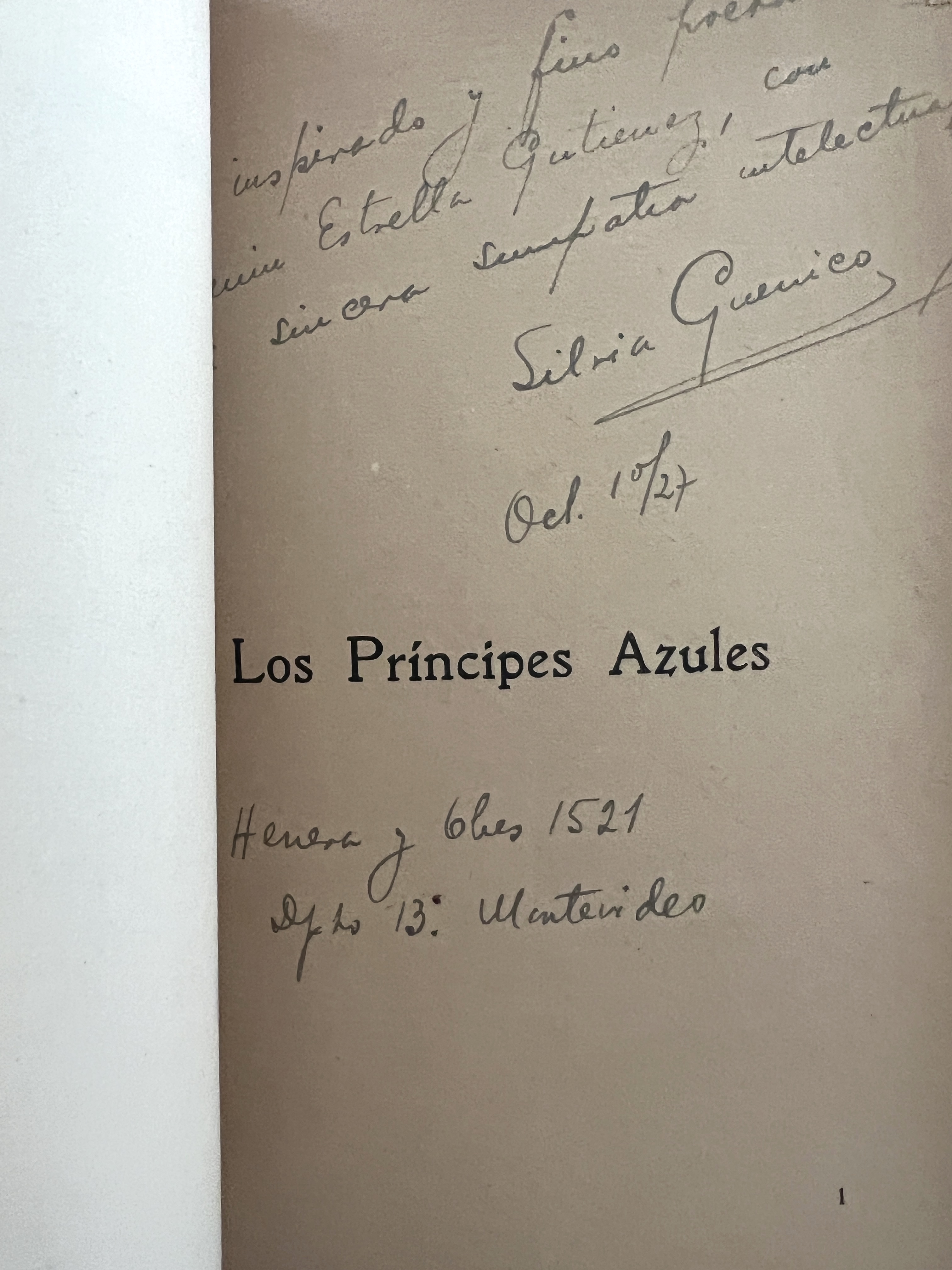

Guerrico, Silvia. Cocktail (Para el atardecer de un sábado inglés): Cuentos Breves. Buenos Aires: Editorial Tor, 1932. First edition. 18.5 cm, 157 pp.; textblock toned with foxing, stories followed by five pages of publicity and press blurbs about Guerrico and an index. Color wrapper with illustration by Luis Macaya (1888-1953), older glue repairs to spine. With signed manuscript dedication from the author to Mané Bernardo on half-title, and a newspaper clipping with a photograph of the author, accompanied by a second handwritten note from Guerrico to Bernardo, both laid in. Note reads “A Mane Bernardo, amiga muy querida, en el atardecer de este sábado inglés en que la alegría de todas hizo editar un segundo cocktail. Cariñosamente. Silvia.” Together with a signed copy of: Guerrico, Silvia. Los príncipes azules. Montevideo: Rossi, 1927. First edition. 20 cm, 139, [5] pp.; in color illus. glued wrapper, illustration by Mario Castellanos. Losses to wrappers, spine, and interior chipped and toned. Reading copy only. Signed dedication by the author on half-title to the poet Fermín Estrella Gutiérrez.

Important association copies of early short stories by radio star Silvia Guerrico (Uruguay, 1905-1983), whose daily program in Buenos Aires became one of the most popular primetime shows in Rio Plata during the medium’s golden-age. Guerrico began her career as a theater critic in Montevideo, where she published Los príncipes azules (Prince charmings) when she was just 22. The collection was well-received by her contemporaries, including Juana de Ibarborou and Blanca Luz Brum. Brum wrote that “since she lives her life touching the painful and burning things, she could very well be a ‘little Russian’ in our literature [otherwise] prostituted by pornography and gauchismo.” (From publicity blurb in Cocktail, p. 157.)

Guerrico moved to Buenos Aires in 1928, where she shifted back and forth between print (incl. a regular newspaper column) and the radio, starting her own “magazine” program in late 1930. This quickly evolved into a daily broadcast called Cartel sonoro featuring many of her own poems and radio plays. Cartel sonoro was part of a wider effort to attract female audiences and consumers to variety shows and narrative programming. By the age of twenty-seven, Guerrico’s program had become a primetime success and an important platform for other women journalists and writers.

Despite her popularity, she was regularly criticized for the “vulgarity” and “femininity” of her on-air persona. Her rise corresponded to a new era of celebrity in Argentinian radio, and the government was just catching up to conservative concerns about the immorality of radio programming and modern music (particularly tango). It was during this period that she wrote the stories in Cocktail, which, like Los Principes Azules, depict modern women drinking and dancing and men who exploit and violate them. In Guerrico’s telling, the only exceptions to this dynamic are men and women of strong moral character brave enough to stand up for themselves. Guerrico’s playful dedication of Cocktail to her “dear friend” the lesbian puppeteer Mané Bernando conjures an intimate world of artist party-going on the “English Saturday”, i.e. the newly created legal right to a half-day off on Saturdays.

The cover illustration of Cocktail reflects the place tango had come to occupy in the Argentinian popular imagination. Associated in the 1930s with violence, the lower classes, and urban areas where prostitution was legal, the racist components of the image were part of the public association of tango with Afro-Argentinian traditions (“tango” and “tambo” were probably initially used to refer to musical gatherings of enslaved people in the Rio Plata).

Rare despite Guerrico’s fame: two copies listed by WorldCat for Cocktail; approx. 6 for Los príncipes. None in modern sales records.

SOLD

Further historical notes on Guerrico and censorship against women:

In 1933, shortly after Cocktail’s publication, Argentina passed laws to limit political speech on the radio and censor tango lyrics. In the spring of 1934, Guerrico interviewed Mexican film star Ramon Navarro for the evening news. Apologizing for recent poor reviews of his local performances, she offered him an impassioned defense that was the start of what became known as the “Guerrico affair”:

“I am going to say to you [...] what women would [say] if nobody was listening, if the mocking gaze of men did not weigh upon them, injuring and humiliating them. . . . Women love you, and there isn’t one who would not [like to say] thank you [...]. For an hour, from whatever movie screen in the world, you have …. erased all realities . . . there were no women who worked like dogs and had to marry some pimple-faced guy; there were no women who waited for the rough kiss of a dirty husband; there were no women overloaded with sadness and children. . . . Men have made life very difficult for women. And day-by-day, they make it uglier.”

Despite the seemingly low-stakes context of a radio interview, the speech’s implications about women’s desire, fantasy, and social silence surrounding their ordinary suffering was incendiary. The radio press called for government investigations. They questioned Guerrico’s qualifications, and women’s more generally, to speak. When she was not immediately fired they criticized her for having dared to “speak for Argentinian women” and described her as a “true threat to the tranquility of the radio listener.” One aggrieved reviewer wrote that Guerrico had proved “women and a microphone are incompatible.” Later that year, there was an executive degree with strict radio regulations to curb offensive content, a move that mirrored the new Hollywood industry guidelines known as the Hays Code. Eventually Guerrico was fired.

She found her way again with a more conservative radio program in the mid-1940s but went into exile after Perón’s election in 1946. After a number of years in Mexico, she eventually settled back in Uruguay.

Cited:

Ehrick, Christine. Radio and the Gendered Soundscape: Women and Broadcasting in Argentina and Uruguay, 1930-1950. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 33-69.