GRAPH BOOKS: PRINTED MATTER FROM RADICAL ART AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS.

FEMINIST HISTORIANS OF MATERIAL CULTURE.

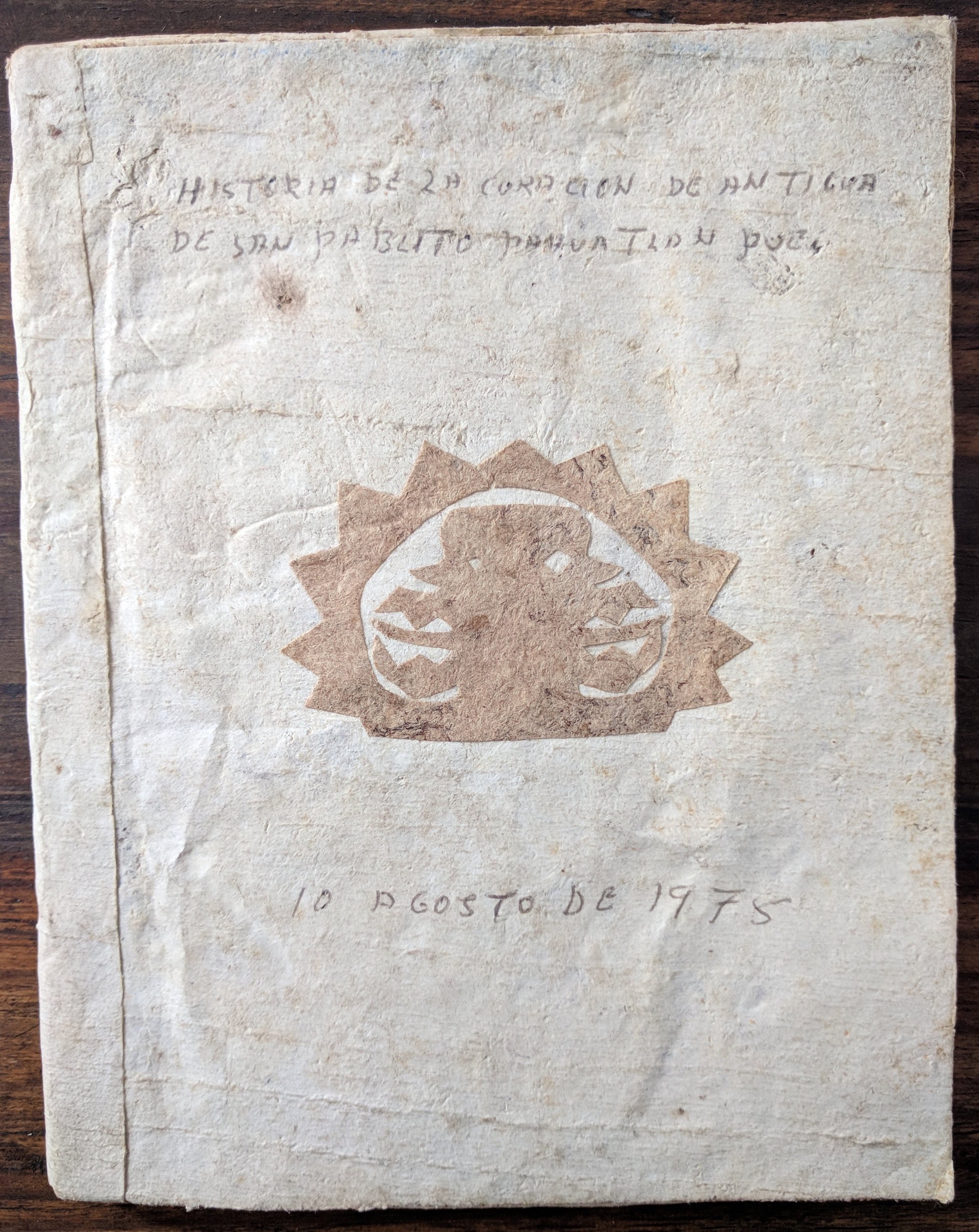

(Brujería) [La] Historia de la Curación de Antigua de San Pablito Pahuatlan, Pue. 10 Agosto de 1975

ca. 1975-1981

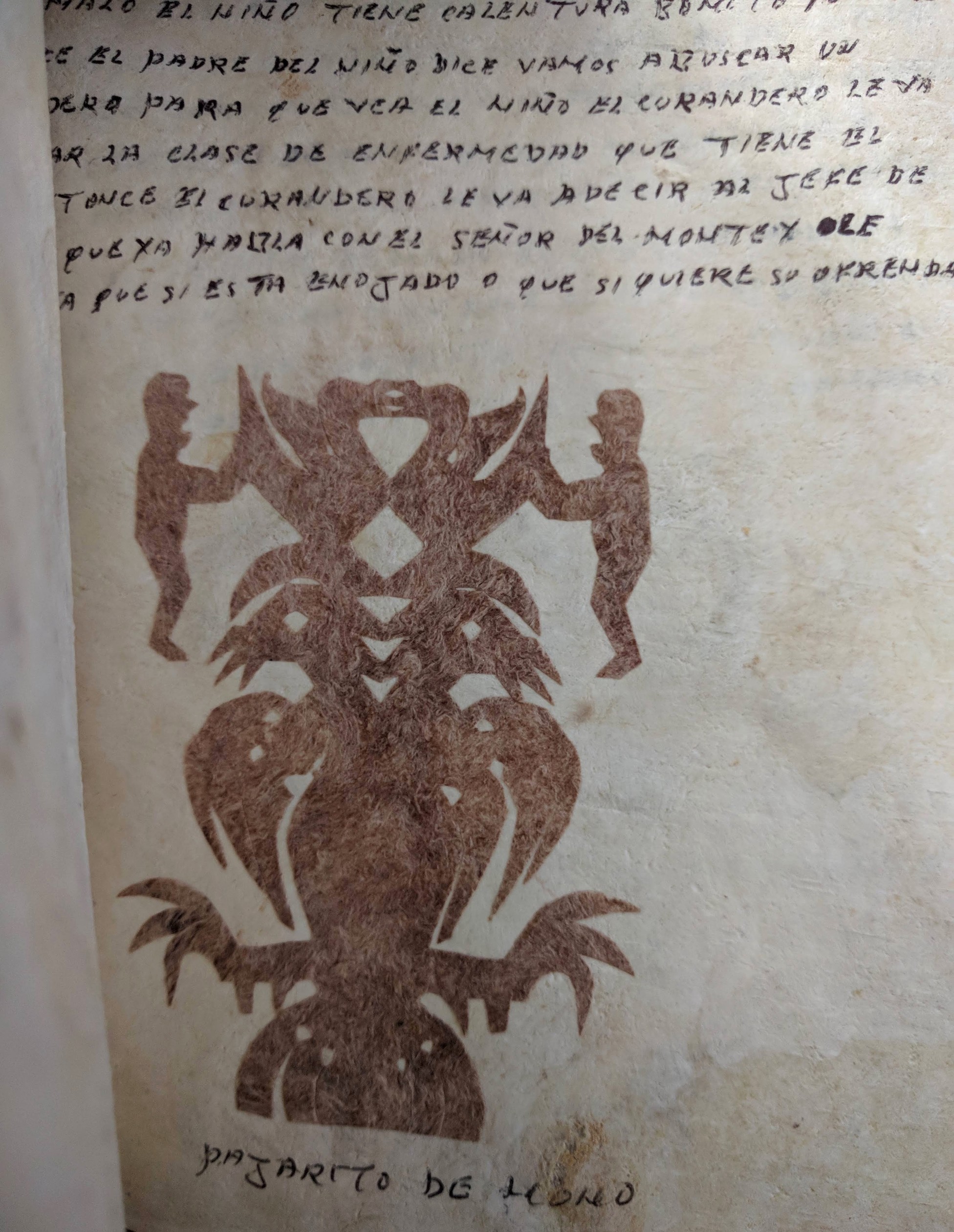

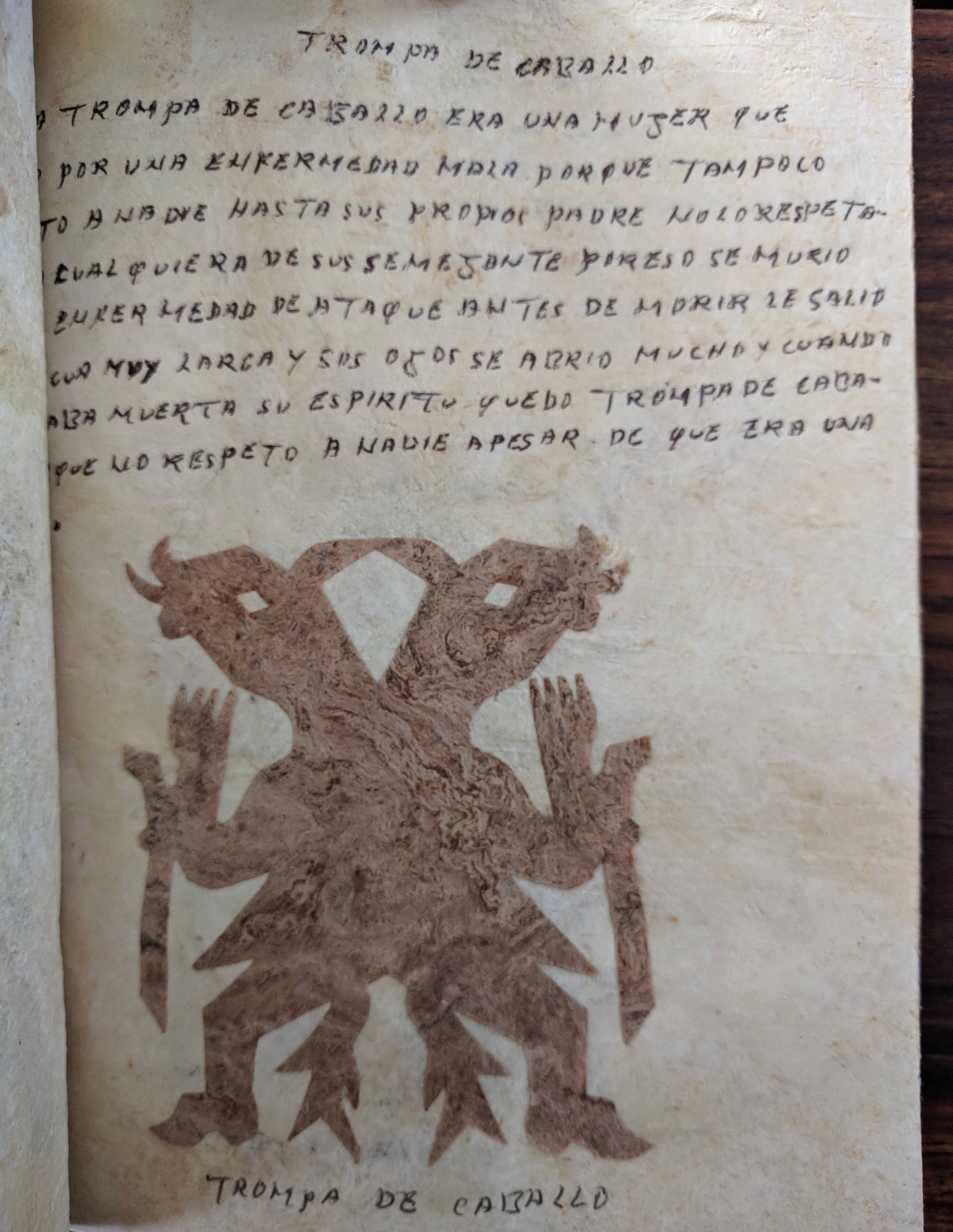

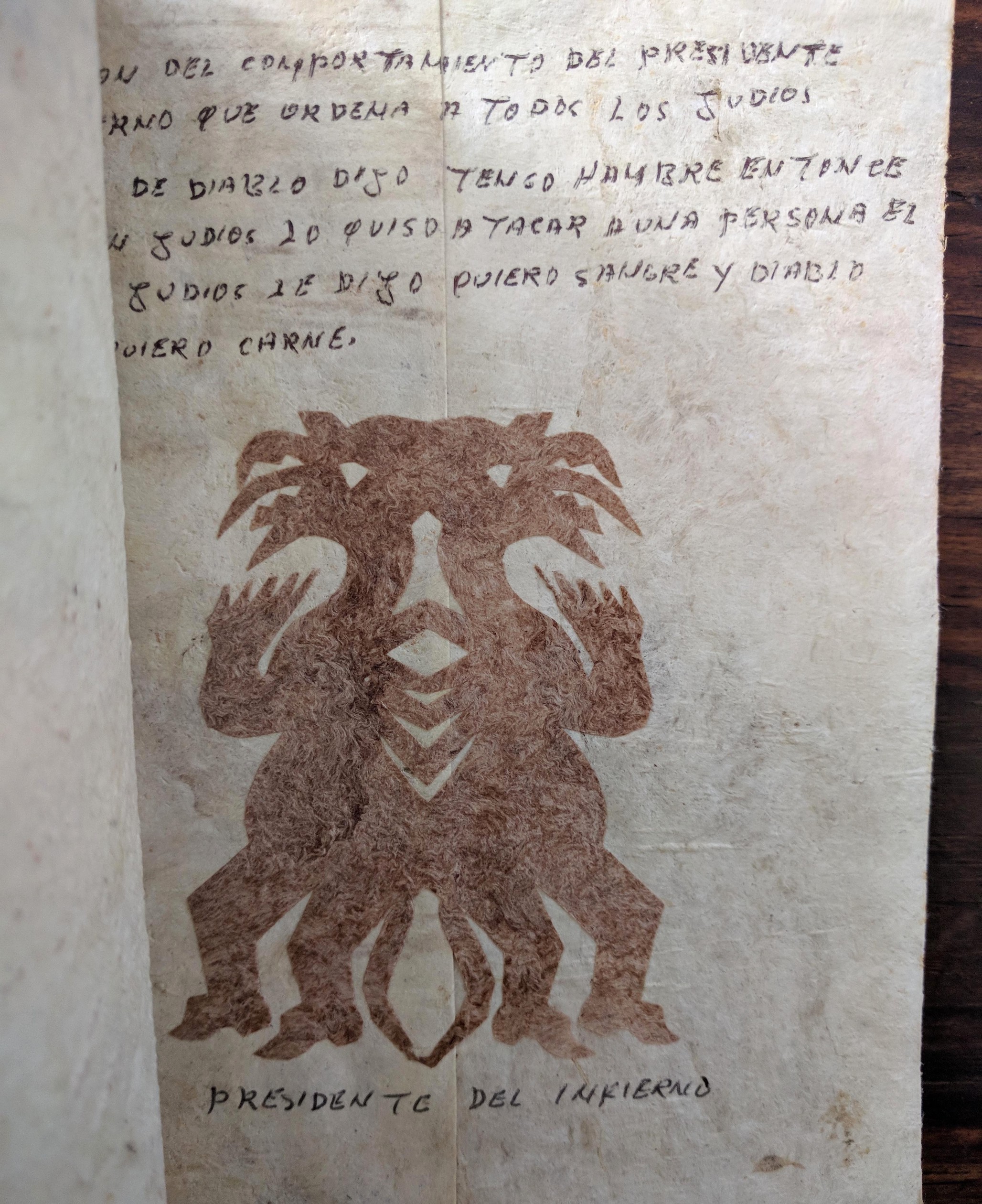

(Brujería) [La] Historia de la Curación de Antigua de San Pablito Pahuatlan, Pue. 10 Agosto de 1975. [cover title]. [Mexico]: ca. 1975-1981. SIZE, [28] leaves; off-white amate with manuscript explanations of magical rituals in black ink, most with dark amate cut-out figures of deities and demons, known as muñecos, odd pages numbered; bound or re-bound in amate wrapper with title and date in pencil on upper cover, near fine.

The Otomí village of San Pablito is famous for its brujería traditions and the preservation of prehispanic paper-making techniques. Shamans (a.k.a. brujos and curanderos) perform ceremonies for sick or cursed persons using cut-out paper figures (muñecos) representing spirit entities drawn from both indigenous and Christian mythos. Before encountering the Otomí prehispanic papers (called amate, from the Nahuatl āmatl) and their magical uses in the early-20th century, anthropologists believed that traditional paper-making had disappeared in Mexico.

In 1975, a well-known San Pablito brujo, Alfonso Garcia Tellez, made the first documented manuscript testimonial of the Otomí paper-based magical practices, “HISTORIA DE LA CURACION DE ANTICUA [sic] DE SAN PABLITO PAHUATLAN PUE.” In it he described the shamanic rituals for various maladies (enfermedades) next to mounted examples of his muñecos. His texts were reportedly dictated to his daughter(s), since he could not write in Spanish, and were gathered in a leporello-style codex in front of the anthropologist Ferdinand Anders. Soon after, at least two other San Pablito brujos also produced manuscripts with muñecos, closely following Garcia Tellez’s format. European and US Bibliographic scholarship has focused on separating the “original” signed versions by Garcia Tellez from these “imitations.” A few of the manuscripts made their way to Mexico City tourists markets in the late 1970s, a few others were collected by anthropologists (including this example). Dating them is problematic because the covers often present with matching manuscript dates from August 1975 or 1978, although at least two are dated as late as 1981.

The present example shares the date and partial title of Garcia Tellez’s first manuscript. It describes the shamanic rituals and their associated gods and offerings and includes approx. 28 muñecos entities in dark amate paper. It differs slightly from other examples, most notably in spelling and the order of the spirits. Every fourth leaf includes a section of joined paper that could be material evidence for it having been created as a leporello (in imitation of prehispanic codexes like the Garcia Tellez examples) and rebound, or it may have been produced as a folio (in imitation of other brujo manuscripts).

Recent Mexican scholarship has called into question earlier bibliographic interest in identifying the “true” San Pablito manuscripts (see Martin, 2014) versus those that were made as imitations. Given that none of the brujos are known to have written Spanish or to have created these spell-books before the mid-1970s, none of the manuscripts are unmediated representations of an original, pre-contact religious practice. On the contrary, each was produced for a commercial and secular market; instead of trying to distinguish the “real’ vs “fake” manuscripts, ethnographers are now creating a correspondence to record all the variations and compare them.

Thus, their value as indigenous, magical testimonies lies not in their singularity, but in these variants: each an artifact of the evolving shamanic practices existing in the community—and that community’s intentional self-presentation to a larger (secular) world.

Martin, Sandra. Historia de la Curación: Antonio López M. Mexico: [Adugo Biri, un proyecto de UNAM], 2014.

SOLD